Book Review von Paul Gipe aus Kalifornien

Wind in Sicht: Landscape in Transition by Ulrich Mertens, A Review

There are some books that simply bring a smile to your face -even to someone as jaded as I. This is one of them. There is a joy in discovering what the future may hold that comes across in Ulrich Mertens‘ Wind in Sicht: Landscape in Transition.

This is a coffee-table book. In it, Mertens compresses a decade of chasing the wind into 160 pages of working landscapes, dramatic compositions, the occasional abstract image, and always the celebration of what man and machine have accomplished in northern Europe. It doesn’t take long to read the English translations of the German text. The focus is on the photos and the landscapes they depict. As any good picture book should, it captivates, it dazzles.

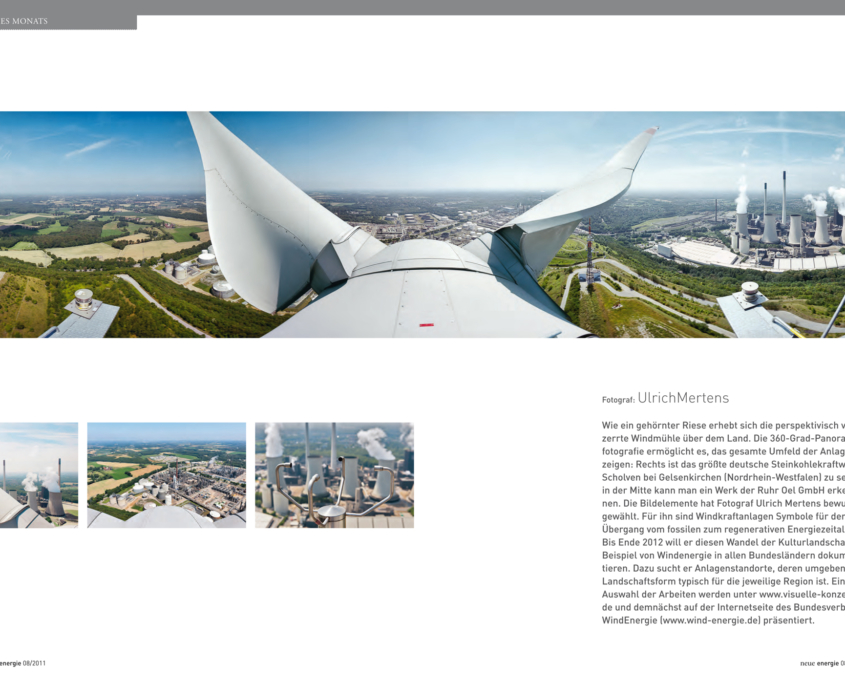

Mertens‘ stunning photos had caught my eye before. I’d seen some of his work in Neue Energie’s „picture of the month“ and thought, „Wow, this guy’s a pro. He had to work to get that shot and he had to have the eye of an artist to frame it and crop it to get that striking effect.“ Mertens calls himself a photographic artist, and when you gaze at his pictures you’ll understand why.

Bild des Monats in „neue energie“ 2011

One of the few photos in the book not taken by Mertens is a view of the photographer hard at work hundreds of meters above the ground, atop a giant Enercon turbine near Bremen. It’s this photo that gives the reader a sense of what it took for Mertens to get the photos in his book. These are not mere snapshots.

And this is Mertens‘ contribution. With his panoramic camera, he has photographed landscapes from the Netherlands to southern Germany from atop modern wind turbines. This is no mean feat. To do so Mertens had to be trained in tower safety and rescue, including–for his offshore photos–how to extricate himself from a submerged helicopter. Working with the wind is a serious business and Mertens had to qualify before he was permitted to scale the turbines with his camera. For this he won Germany’s Renewable Energy Agency photo journalism award in 2013. His work continues to focus on the link between people, technology, and nature.

In one eye-catching view, Mertens captures a Vensys nacelle being positioned on top of a tubular tower from his crane-side perch. Inside the tower are five windsmiths with a full complement of attachment bolts. They look up expectantly. Could this be a metaphor of how we look expectantly at renewable energy as a means for addressing climate change?

In another equally dramatic series, Mertens‘ camera looks skyward as a three-blade rotor is being lifted to a nearby nacelle. Mertens captures the sweep and curve of the massive blade in the same way other photographers have shown the curves and shadows of the human form.

And what may well become Mertens‘ iconic photo is a view, from atop a tower, of three wind turbine blades lined up on the ground. Their red and white obstruction marking form an abstract composition as a lone figure in a red jacket walks by. The figure adds that bit of motion to an otherwise post-modern still-life.

Mertens‘ book documents the visual evidence of how scattered clusters of wind turbines are transforming a German landscape once dominated by the cooling towers and steam plumes of conventional power plants.

Windpark Cottbusser-Halde und Cottbus-Nord mit dem Vattenfall Braunkohlekraftwerk Jänschwalde

It’s good to see that professor Olav Hohmeyer sponsored Mertens‘ project. Hohmeyer is one of Germany’s academic pioneers of renewable energy. He was one of the first to place a value on the benefits to society of renewable energy. His groundbreaking work called into question the assumptions of classical economists. Since then many have followed in his footsteps, showing that renewable energy is far more valuable than the benefits of the electricity alone. For his part, Mertens shows that there is an intrinsic beauty to modern wind turbines, just as Hohmeyer showed that the true value of renewable energy was hidden from view.

I couldn’t help but smile in wonder at the photos. I know something of the work it takes to get those shots. And I know what they mean. Deep down they give a sense of the breadth and depth of today’s wind industry and of the men and women making it happen. Mertens has captured that and done so beautifully.

Unbeknownst to Mertens, the book’s cover photo has a special meaning to me. At the lower left is a traditional sailing vessel common in the coastal waters of the Wadden Sea that stretches from the northern Netherlands to Germany’s northwest coast. The vessel’s sail says Eems No 1, likely a reference the Dutch port of Eemshaven where one of Europe’s largest gas-fired power plants is located. It’s also where a row of Micon turbines was installed along a drainage canal in the late 1980s.

I saw a photo of these machines in Windpower Monthly and determined I wanted the same shot. The photo was illustrative for several reasons. It was an example of a linear array mirroring a linear feature of the landscape–the canal. It also powerfully conveyed the concept of the new wind turbines replacing the old fossil-fired power plant in the background. I’ve used my photo of this array many times over the decades and it can be found in my newest book as well.

Buchcover „Wind in Sicht – Landscape in Transition

Mertens‘ cover photo says something similar. It pairs the old, the sailing vessel, with the new, a modern wind turbine in the foreground. And he places both in the low-lying landscape of northern Europe. The wind turbine stands on land so low-lying that it could well be at sea.

My connection with this region goes even deeper and encompasses the policy and political battles that played out on the lowlands facing the Wadden Sea. The contrast between how the Netherlands chose to develop wind energy and how Germany did across the bay, is stark. One was dominated by an arrogant but powerful electric utility, the other by farmers and villagers raising wind turbines for their own benefit. (For my take, see Fluttering Flags, Can-can, & the Big Men of Wind Energy and Remarks by Paul Gipe at the Dedication of EDON’s Wind Plant at Eemshaven, the Netherlands.) The Dutch utility failed spectacularly, while German farmers built the foundation of a profitable industry from the ground up.

Germany’s people-powered renewable energy revolution has produced a number of artists and entrepreneurs such as Mertens. His career itself follows that of Germany’s energy transition–or Energiewende–that he seeks to document. Mertens began by photographing coal miners deep underground. He has gone from the bowels of the earth to the heights of modern wind turbines. Perched precariously atop wind turbine nacelles, he has scanned the horizon with his panoramic camera. In doing so, Mertens gives us earthbound observers a view we wouldn’t otherwise have, just as he once gave viewers a glimpse of life in the darkness of a coal mine.

The book’s title is a subtle play on words. Sailors in distress on the storm-tossed North Sea would shout „land in sight“ when a welcoming harbor came into view. Mertens makes the analogy: A society, beset by climate change and environmental disruption, sees wind turbines in the distance–a life-buoy for the planet’s salvation.

Mertens explains that he wanted to use his panoramic camera to capture the „return of the windmills“ to the German landscape. To Mertens, and of course to many others, windmills were an essential part of the landscape in the 16th and 17th centuries. Visit any museum collection of the period, including paintings by the Dutch Masters, and you’ll see that windmills were a not only a prominent feature but sometimes the principal subject of the work.

Professor Martin Prominski, in his comments on Mertens‘ book, observes that wind turbines „touch our deepest emotions.“ He’s referring to the angst and sometimes the outright hostility engendered by the idea of putting wind turbines on the landscape, but he could just as well be commenting on how we see them as harbingers of the future, of how we can live in harmony with the land. In this, Mertens‘ book and its included commentary is the natural successor of Frode Birk Nielsen’s The Nature of Wind Power on the role of wind energy in the landscape. Art historian Silke Lahmann-Lammert, in her commentary, describes wind turbines as „vertical arrows“ that are a „powerful, slim, [and] dynamic,“ messengers of a new era.

We just don’t see books like Wind in Sicht on this side of the Atlantic. It’s a credit to Europeans that they still value books like this. Mertens‘ Wind in Sicht capably follows in the footsepts of Jan Oelker’s monumental Windgesichter (The Face of Wind Energy) and Philippe Rocher’s L’Energie du Vent. Both books have a place of honor on my bookshelf. I will make a place for Mertens‘ Wind in Sicht as well.

Mertens, Ulrich. Wind in Sicht: Landscape in Transition. Daun, Germany: Eifelbildverlag, Edition Bilderperlen, 2017. 160 pages. ISBN: 978-3-946328-23-0. 39.90 € cloth. 29.5 mm x 24.5 mm x 2.2 mm (11.5 in x 9.5 in x 0.75 in). 1.28 kg (2.83 lbs). Printed in the Czech Republic. www.windinsicht.de.

© and published by Paul Gipe at www.wind-works.org

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar

An der Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlasse uns deinen Kommentar!